INFLORESCENCES

(flower clusters)

(scroll down for summary diagrams)

The manner in which flowers are arranged on plants varies tremendously, and is often a key feature used to identify plants. Moreover, some inflorescences are associated with particular plant families, for example: umbels in the carrot family (sometimes thus called the “Umbelliferae”); spikelets in the grass and sedge families, and; a spathe/spadix combination in the arum family. First, some basic terminology.

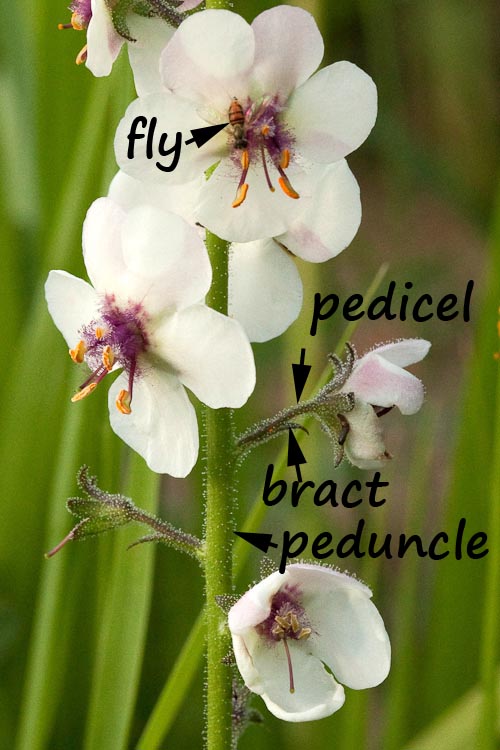

A PEDICEL is the stalk of an individual flower. A PEDUNCLE is the stalk of an entire inflorescence. Often, there will be a small leaf-like BRACT subtending a pedicel.

Moth mullien inflorescence.

I. SOLITARY INFLORESCENCES

(terminal and axillary)

Some inflorescences are one-flowered, in which case the pedicel may (oddly, it seems) also be regarded to be a peduncle. Solitary inflorescences can be terminal, as in the genus Trillium. Here’s large-flowered trillium (T. grandiflorum) proudly displaying its TERMINAL SOLITARY inflorescence. Note also in this species that the flower is stalked, i.e., having a pedicel (which in thus case is also a peduncle).

Large-flowered trillium solitary, stalked terminal inflorescence.

A contrast that illustrates well another condition with respect to flower stalks is provided by another trillium, the aptly named “sessile trillium,” Trillium sessile. “Sessile” is term that, in botany, means “stalkless,” i.e., lacking an evident pedicel in the case of flowers (or lacking a petiole if it’s a leaf that’s being described).

Sessile trillium flowers are non-stalked (sessile), solitary, and terminal.

Flowers may be placed singly in the axils of normal foliage leaves, as in this Gattlinger’s false-foxglove (Agalinus gattlingeri, family Orobanchaceae).

False foxglove flowers are SOLITARY in the leaf AXILS.

II. SCAPOSE INFLORESCENCES

(leafless and bractless flowering stems)

A SCAPE is a bare flowering stem arising from a cluster of leaves at the base of the plant. Scapes may either one-flowered, or few-several flowered. The so-called “stemless” violets exemplify the solitary scapose inflorescence type.

Pale white violet is a “stemless,” having a SCAPOSE inflorescence.

III. ELONGATE INDETERMINATE (RACEMOSE) INFLORESCENCES

(raceme, panicle, spike, catkin/ament, spikelet, spathe & spadix)

Plants grow by adding cells at their tips. These regions of cell division are called “apical mersitems.” Thus, a typical plant stem that is producing flowers as it elongates will have: (a) no precisely set, predetermined number of flowers, i.e., it is of “indeterminate” length and flower number and; (b) the lower portions are actually older than the upper portions. (That’s so very un-animal-like! Are your feet older than your head?) The most typical plant inflorescences are thus indeterminate, and sometimes called “racemose,” after the most representative type, the RACEME.

Members of the mustard family often have their flowers in bractless racemes. This is smooth rock-cress (Arabis laevigata); note there are developing fruits at the bottom, flowers in the middle portion, and unopened flower buds at the tip of this very evidentally indeterminate inflorescence type.

The smooth rock cress inflorescence is a bractless RACEME.

Wild hyacinth, Camassia scilloides (Liliaceae/Hyacinthaceae) is racemose, and the individual flowers are subtended with bracts.

Wild hyacinth flowers are borne in RACEMES, with bracts beneath each flower.

Imagine a raceme that’s having so much fun making flowers that just being one simple elongate axis isn’t good enough; it wants to branch out, and so it does. A PANICLE is a repeatedly branched elongate inflorescence. (Fun memory clue: imagine the flowers are in a panic, and running off in all directions.)

The photo is a bit too much of a far-down (is that the opposite of a close-up?), but lo (and behold) the amazing panicle (several shown here actually) of water plantain, Alisma triviale (Alismataceae).

Water-plantain produces a multitude of small flowers in a PANICLE inflorescence type.

Here’s another paniculate species: figwort, Scrophularia marilandica (Scrophulariaceae, the figwort family).

Figwort flowers are produced in an elongate PANICLE inflorescence type.

Imagine a raceme, but with flowers that are sessile (stalkless). Or better yet, look at a picture of a SPIKE.

Moth mullein flowers are in a SPIKE inflorescence type.

The orchid genus Spiranthes is called “ladies’-tresses” because some imaginative botanist way back when saw a resemblance to braided hair. This is spring ladies’s-tresses, Spiranthes vernalis.

Ladies’-tresses is an orchid with a SPIKE inflorescence type.

Cat-tails produce unisexual flowers in contiguous portions of an especially elongate spike: male (staminate) above; female (pistillate) below.

Cat-tails produce tiny wind-pollinated flowers in an elongate SPIKE inflorescence type.

The spike is pistillate below, and staminate above.

There are some interesting variations on the spikelet theme. A CATKIN (also called an AMENT) is a small, drooping spike with (typically) tiny unisexual wind-pollinated flowers. Many trees produce only their make flowers in catkins, such as this bittternut hickory, Carya cordiformis (Juglandaceae, the walnut family).

Bitternut hickory’s male flowers are in CATKINS.

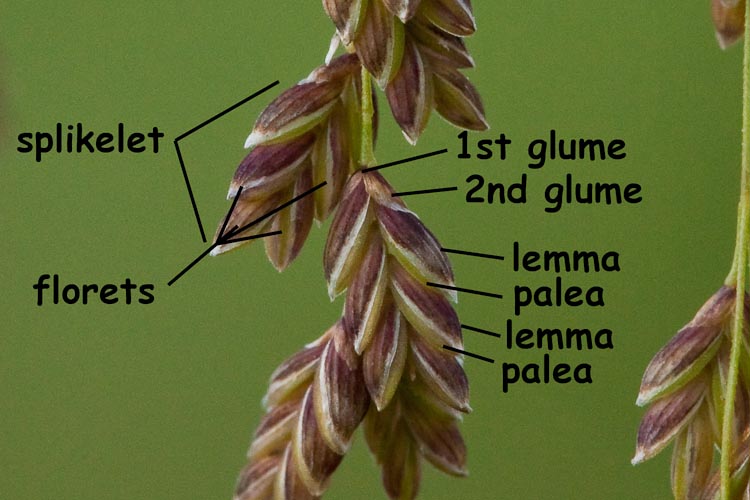

The flowers of grasses and sedges are highly modified, and aggregated into tiny clusters appropriately called SPIKELETS. Here’s a few grass spiketes, with some extra parts labelled. Skip over all the details for now except for “spikelet” and “floret” (which can be thought of as a flower.

Grass flowers are in arranged in a tiny spikes each called a SPIKELET.

Sedge flowers too are in SPIKELETS.This is shining sedge, Carex lurida.

Sedge flowers are in arranged in a tiny spikes each called a SPIKELET.

Oooh, oooh, SPATHE and SPADIX! Who doesn’t love Jack-in-the-pulpit? Members of the Arum family (Araceae) have a specialized upright spike (in this case the preacher “Jack”) called a SPADIX that is surrounded and partly enveloped by a huge leaf-like bract, the SPATHE (the pulpit).

Each Arisaema spadix is either pistillate (hello, Jill in the pulpit?) or male. Below, see a pistillate spadix before and after some sociopathic botanist had at it with a pocket knife. Note the plump ovaries topped by a stigmatic surface.

The Arisaema inflorescence is a SPADIX surrounded by a leaf-like SPATHE.

This individual is pistillate (female).

This is a male inflorescence.Note the abundant stamens, which have mostly released their pollen.

The Arisaema inflorescence is a SPADIX surrounded by a leaf-like SPATHE.

This individual is staminate (male).

IV. DETERMINATE (CYMOSE) INLORESCENCES

(cyme, helicoid/scorpioid cyme)

Some inflorescences, instead of having their youngest parts at the growing tip and thereby being indeterminate with respect to the number of flowers they can produce, instead have the oldest portion terminal. This “determinate” growth form is called a CYME, and in its simplest manifestation, consists of three flowers, like the running strawberry-bush, Euonymus obovatus, family Celastraceae) shown below.

The running strawberry-bush inflorescence is a simple 3-flowered CYME

Most cymose inflorescence are repeatedly branched, and might be mistaken for a panicle or some other inflorescnce type. They can be difficult to interpret. An interesting and distinctive modified cyme is an elongate one termed that is coiled, and thus called a HELICOID CYME or a SCORPIOID CYME. This is the characteristic inflorescence of the forget-me-not family, Boraginaceae (including the water-leafs, formerly Hydrophylklaceae). Comfrey (Symphytum sp.) is an example.

The comfrey inflorescnce is a HELICOID CYME.

V. FLOWERS ALL ATTACHED AT THE SAME POINT

(umbel and head/capitulum)

An inflorescence in which several-many pedicellate (stalked) flowers are attached at the same point on a peducnle is called an UMBEL. The umbel is a fairly common inflorescence type. Simple umbels are produced by many clovers (genus Trifolium in Fabaceae, the legume family).

White clover flowers are stalked, and all attached at the same location on the peduncle,

thus the inflorescence is an UMBEL.

Here’s another example of an umbel, this time produced by the most magnificent organism in the entire known universe (eat your heart out, blue whale!; hang your cones in shame, coast redwood), Sullivant’s milkweed, Asclepias sullivantii (Apocynaceae, the dogbane family).

Sullivant’s milkweed flowers are arranged in a simple UMBEL.

The most well-developed umbels are the compound ones produced by many members of carrot family, Apiaceae. Indeed, this family has an alternate name, the Umbelliferae, which literally means “umbel-bearing.” Wild carrot, also called “Queen Anne’s lace,” produces compound umbels with both the primary and secondary “rays” (peduncles) of the umbel subtended by a series of leaf-like bracts (termed an “involucre).

Wild Queen Anne’s lacy carrot produces a compound UMBEL.

Imagine an umbel, but with flowers that are sessile (stalkless). Or better yet, look at a picture of a CAPITULUM. This is common teasel, Dipsacus fullonum (Dipsacaceae, the teasel family).

Teasel flowers are in a compact CAPITULUM.

Undoubtedly the most noteworthy plants to present their flowers in a capitulum are those in the aster family, Asteraceae. Also called the “Compositae” because their capitulum often includes two types of flowers in a special mixed cluster, these capitula often resemble large individual blossoms. The flowers are individually tiny; aggregation in a capitulum facilitates assembly-line pollination, whereby one floral visitor can deliver pollen to, and remove it from, many flowers in one foraging bout.

Honeybee visits sunflower CAPITULUM, which consists of a great many small flowers.

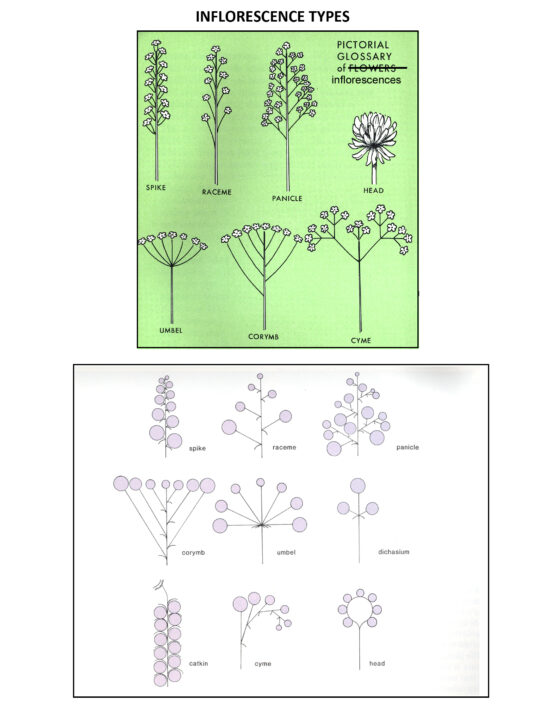

Below are two diagrams from field guides (I forget which ones or I would have cited them). The top one has a major flaw: no bracts! The bottom one is OK but that hair-splitting difference between CYME and DICHASIUM is a bit much (determinate inflorescences are confusing enough, thank you.)

Inflorescence types