FABACEAE

(legume family)

The fabulous Fabaceae includes trees, shrubs, herbs and vines, many with nitrogen-fixing bacterial root nodules. The leaves are alternate, usually pinnately compound or trifoliolate, and stipulate. The flowers are bisexual (hermaphroditic), in racemes, heads, umbels, or panicle inflorescence types. The calyx consists of 5 connate (fused) sepals; the corolla is made up of 5 mostly separate petals. The androecium is (except in one subfamily) composed of 10 stamens, often bundled together in a single group (monadelphous) by having their filaments joined into a tube surrounding the gynoecium or, as is more often the case, joined in two groups (diadelphous) including a set of 9 such bundled stamens, plus one wholly separate lonely little stamen standing all by itself, feeling like an outsider, and hoping that someone, anyone, would “friend” him on Facebook.” The gynoecium is unicarpellate, and the fruit is (famously) a legume.

See this pretty little flower, with bilaterally symmetric flowers of separate petals, one of which is much larger than the others. It is obviously a legume of some sort. It was rather abundant in a field.

Lovely little legume in a field in central Ohio, late spring.

Here’s the field it was growing in.

The field it was growing in, late spring.

O.K. ha ha. It’s just a soybean field. You knew that, didn’t you? But we hardly ever look closely at a soybean plant, at least not in flower. In fruit, they’re a lot more distinctive, as seen during October.

Soybean fruits in October.

…and the field these were growing in:

Autumn soybeans.

Autumn soybeans.

The soybean is a very ancient “cultigen,” i.e., a plant that has been deliberately altered through artificial selection. It originated from a wild Asian species, Glycine soja. Although soybeans are high in protein and glycine is the name of an amino acid (the building blocks of proteins), the generic name “glycine” is actually derived from a Greek work meaning “sweet.” However, the sweet thing that prompted Linneaus to come up with that crazy name was actually the tuber of a wholly different legume –a North American vine now known as Apios americana (groundnut) –which he originally classified as Glycine apios.

The Fabaceae is very important economically as well as ecologically, thanks to peas and beans of all kinds (e.g., kidney, lima, garbanzo, broad, mung), lentils, peanuts, alfalfa, sweet clover, licorice. Carob, which is widely used as a chocolate substitute (but why would anybody want to substitute something for chocolate?), is also a member of this family. But having edible members does not mean that a family is uniformly safe to eat. Locoweeds are legumes that have been responsible for the death of many horses, cattle, and sheep, particularly in the southwestern U.S. Other poisonous legumes include lupine, black locust, and mescal beans.

While indigo, the blue associated with blue jeans, is now mostly derived from synthetic dyes, the original natural source was the Indian plant also called “indigo,” Indigofera tinctoria.

The large family is divided into three subfamilies.

- subfamily Papilionoideae, our most numerous and most typical legumes, with strongly bilaterally symmetric flowers configured with the large upper petal (banner) situated outside of the lateral ones (the wings), and the stamens, in most instances, diadelphous (9+1)

- subfamily Mimosoideae, consisting of tropical trees and shrubs with many colorful stamens. Silk-tree (Mimosa) is sometimes planted in Ohio, and prairie bunchflower (Desmanthus) is a warm-season prairie herb.

- subfamily Caesalpinoidae, distinguished from the papilionoideae by by having the corolla more nearly regular (radially symmetric) than the very strongly bilaterally symmetric legumes (fruits), by having its upper petal inside (not outside) the 2 lateral ones, and by having the 10 stamens free from one another (not partly fused in two groups). The family is primarily an old-world tropical one. In Ohio we have five native genera, of which two —Cassia (wild senna), and Chamaecrista (partridge-pea) are herbs, and three —Cercis (redbud), Gleditsia (honey-locust), and Gymnocladus (Kentucky coffee-tree) –are trees.

SUBFAMILY PAPILIONOIDEA

(our most numerous and also most typical legumes)

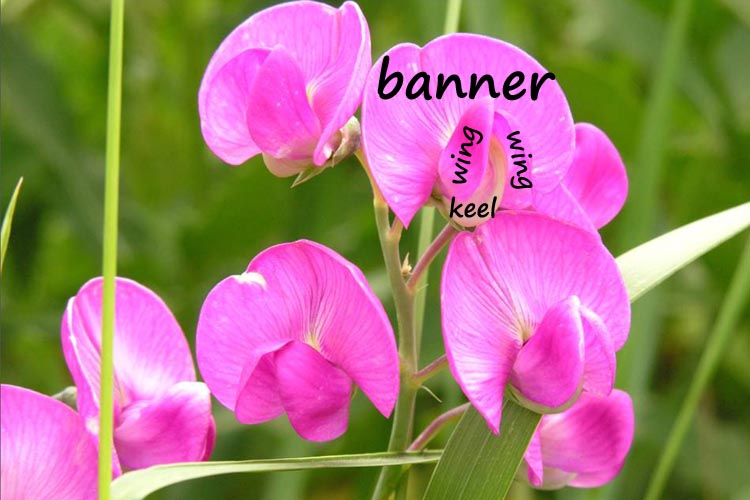

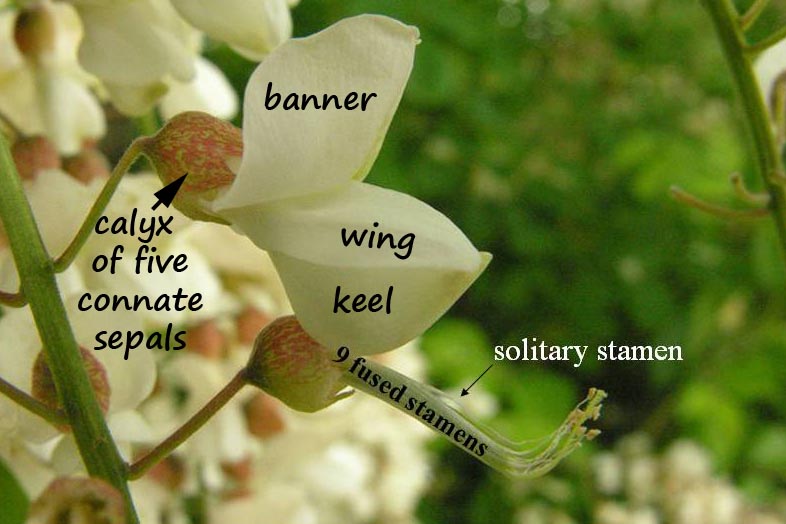

Pea family flower structure. Papilionoid? Yes, papilioid. It means “butterfly-like,” and it refers to a type of bilateral flower symmetry in which the lateral petals are especially prominent, like a butterfly’s wings. The flowers of papilionoid legumes are 5-merous with mostly separate petals. Mostly separate …what does that “mostly” mean? We’ll get to that. First, see large uppermost petal called the “banner.” This is flanked by two lateral (side) petals called”wings,” all of which are situated above a pair of lowermost petals that fit closely against the sexual parts of the flower, and that are fused, but only at their tips, thereby accounting for the “mostly” in “mostly separate.” These petals are labelled below, on everlasting pea, Lathryus latifolia.

Banner wing wing keel.

Here’s another example, the rugged tree blacklocust, Robinia pseudoacacia.

Banner, wing, wing, keel.

Showy tick-trefoil, Desmodium canadense, is another example.

Banner, wing, wing, keel.

The characteristic fruit of the legume family is, well, duh, a legume. This is a dry fruit that develops from a unicarpellate gynoecium, and typically splits along two lines (sutures). A legume, and by extension the concept of a carpel, is best understood by examining a common legume seen at the grocery store: the pea.

A carpel is a modified seed-bearing leaf.

A carpel is a modified seed-bearing leaf.

The legume fruit consists of a single carpel.

Indeed, legumes often look rather like what they are, evolutionarily: a folded-over leaf forming a chamber, completely enclosing a row of seeds produced along the margins of that folded-over “leaf. Below, see hairy vetch, Vicia villosa, and introduced weed that is common along roadsides and in meadows. The vetch inflorescence is a raceme.

MOUSEOVER the IMAGE to see VETCH FRUIT

The hairy vetch inflorescence is a raceme.

The fruit is a legume

Common papillionoid legumes I: trifoliolate, mostly weedy herbs

(clovers and sweet-clovers, medicks, and bird’s-foot trefoil)

Trifolium is the clover genus. The genus name refers to its trifoliolate leaves. The flowers are in heads or head-like umbels. In Ohio, we have 10 species of Trifolium, all but two of which are non-native and generally weedy. We found a beachball in the woods. It made a nice backdrop for this white clover, Trifolium repens.

Clovers have trifoliolate leaves, and flowers in compact umbels.

A photo taken of white clover a little farther along in its flowering schedule shows a feature that distinguishes Trifolium from some similar legumes: in fruit, the corolla is persistent (doesn’t fall off), and, while somewhat brownish and withered, drapes over the developing legumes.

Trifolium, in fruit, retains the corolla.

Red clover, Trifolium pratense is especially robust, with larger and darker flowers than most, as is evident in the picture below. Or not. I chased a black swallowtail nectaring on red clover. The butterfly is very fond of the clover, so you could say it loves clover. Several times I had to move the butterfly in order to get a better picture of the clover. Being near Wright-Patterson Air Force Base, there was a lot of air traffic, including a helicopter sent to keep and eye on me, piloted by a man named Rover. To monitor my activities from the air, the flight dispatcher’s instruction to the chopper pilot were simple: “Hover over clover-lover mover, Rover!”

MOUSEOVER the IMAGE for a BETTER VIEW

Black swallowtail butterfly nectaring on red clover.

Red clover is one of two somewhat similar common clovers; the other is Alsike clover, Trifolium hybridum. Both are somewhat pink-flowered, robust, and weedy. Alsike clover is somewhat smaller, and the leaves lack the dark “chevrons.” Here they are side-by-side.Also, note they are also distinguished on the basis of their stipules (MOUSEOVER).

MOUSEOVER IMAGE for a COMPARISON of their STIPULES!

Red clover compared with Alsike clover: larger, darker, and with pale chevrons on the leaves.

Clovers also come in yellow, which can be a bit confusing, because there’s another trifoliolate blonde legume around town, this one in in the genus Medicago. Called “black medick,” Medicago lupulina, the prinncipal difference is seen in fruit. First, see hop clover and notice how, in true Trifolium fashion, the old corolla doesn’t fall off but instead remains in the drooping old flowers, covering up the fruit.

Hop clover, in typical Trifolium fashion, retains its corolla after flowering is over.

(This is supposed to resemble hops –the beer-flavoring ingredient.

Contrariwise, the corolla of black medick, Medicago lupulina, fall off after flowering, exposing twisted little fruits that eventually turn black.

Black medick looks like clover, but its corollas fall away, exposing the fruits.

The genus Melilotus also is composed of trifoliolate herbs, but these have their flowers in racemes, not umbels or heads. There are two very common species in Ohio that are easily separated by flower color. Yellow sweet-clover, Melilotus officinalis, and white sweet-clover, M. alba.The yellow one appears a bit earlier in spring than the white.

Sweet-clover times two.

Technically, bird’sfoot-trefoil, Lotus corniculatus, is not trifoliolate, with prominent stipules. It’s 5-foliolate, without stipules, and the leaves are sessile. O.K. Anyhow, it looks like this:

Birdsfoot trefoil is widely planted for erosion control and soil enrichment.

Curious why is it’s called birdsfoot?

The fruiting stems resemble birds’ feet!

The fruiting stems resemble birds’ feet!

Common papillionoid legumes II: pinnately compound weeds.

(vetch and crown-vetch)

“Vetch” is a common name for at least two genera of sprawling or vine-like herbs with pinnately compound leaves. Vicia species have their flowers in elongate racemes. Cow vetch, Vicia cracca is especially common. Look for pinnate leaves with the terminal leaflets modified into tendrils, and purple flowers in elongate racemes.

Cow vetch is a sprawling vine-like herb with tendril-tipped pinnately compound leaves.

Oh, this is neat. There’s a vetch that has its flowers not in elongate racemes, but in simple little axillary pairs. But that’s not the neat part…the neat part is EXTRAFLORAL NECTARIES!!!!!!! These are plant organs that produce a sugary fluid that insects consume, but which are not located in flowers and that do not reward pollinators. Instead, the nectar-like insect food is, in effect, payment to body-guards.

Ant foraging on extrafloral nectary of narrow-leaved vetch.

Here in an open meadow, ants visit the nectaries. It is generally the case that, by providing a food source for ants, the plant receives a benefit: protection by the ants from plant-eating predators.

Ants foraging on narrow-leaved vetch extrafloral nectaries.

Another “vetch” is Coronilla varia, crown vetch. This sprawling pinnate-leaved herb produces showy two-toned flowers in compact umbels. It is quite weedy in open areas.

Most, but not all our vetches are weeds. There’s a nice native one called Carolina vetch. It’s a little smaller than the weedy ones, and has white flowers.

Yippee! A native vetch. Ahhh.

Other Lovely Native Papillinoid Legumes

(false indigo, beggar-ticks, and ground-nut)

A special feature of the roots of legumes is of benefit to soil fertility. Bacterial living symbiotically in swellings (nodules) in legume roots can extract nitrogen from the atmosphere, allowing this essential element into the ecosystem. Nitrogen-fixing abilities give the legumes an edge in nutrient-poor soils, the fabulous Fabaceae is one of the most prominent forb families in midwestern tallgrass prairie. (A “forb” is an herbaceous plant that is not a grass or similar plant. i.e., what is usually meant by the term “wildflower.”) This is false white indigo at the Larry R. Yoder Prairie at the Marion Campus of Ohio State University.

False white indigo is a perennial prairie forb.

Round-headed bush-clover is a common but inconspicuous wand-like legume found in high-quality prairie. It can be seen flowering in August.

Round-headed bush-clover (Lespedeza capitata) is a native prairie wildflower.

Round-headed bush-clover (Lespedeza capitata) in fruit.

In autumn through winter the dried plants are distinctive owing to their capitate clusters of fruits.

In the genus Desmodium we see an interesting (perhaps “annoying” would be a better word) variety of the legume fruit. Instead of splitting along the edges to release seeds, these fruits are termed “loments,” distinguished by the fact they split apart into dry single-seeded units.

MOUSEOVER the IMAGE to see TICK-TREFOIL in FRUIT

Showy tick-trefoil is a native prairie forb.

Desmodium is called “tick-trefoil” because, reminiscent of ticks, they are flat and adhere to passers-by in a rather aggravating manner. The photo below is another species of tick-trefoil from the one above (note the more angular segments), stuck to a sleeve.

Sticking tick-like to a sleeve, tick-trefoil is adapted for zoochory (animal seed dispersal).

Ground-nut, Apios americana, is a native vine that bears 5-7 parted pinnately compound leaves, and racemes of moderately large flowers that are predominantly brown-purple.The small underground potato-like ground-nut tubers are regarded as choice edible items, said to have been a staple of Native Americans. The name “ground nut” is also used for a wholly different legume, the peanut (Arachis hypogaea), in many parts of the world.

MOUSEOVER the IMAGE to see GROUND-NUT FLOWERS

Ground-nut is a native twining vine with oddly colored flowers.

Subfamily Mimosoideae

(Note to self: find some of these, and take their pictures!)

Subfamily Caesalpinoidae

In this subfamily the corolla more nearly regular, the banner is placed inside the two wings, and the 10 stamens are free from one another. Our two herbaceous genera are primarily found in prairies. One of them, wild senna, is a tall perennial.

Wild senna is a tall prairie forb.

The bumblebees love wild senna.

The bumblebees love wild senna.

Wild senna also seems to have gone to great lengths to attract some non-pollinating insects. At the base of the leafstalk are globose structures that produce some substance that is sought by ants. This is another example (see narrow-leaved vetch above) of extra-floral nectaries, structures that secrete food for ants, apparently to foster their presence on the plants as a defense against herbivorous insects.

Wild senna extrafloral nectaries are avidly visited by ants

Legumes to Know and Love

(or not love as the case may be)

Showy tick-trefoil, Desmodium canadense, is a prairie wildflower.

Round-headed bush clover is a small-flowered tall prairie wildflower.

The dried plants are distinctive owing to their capitate clusters of fruits.

Round-headed bush-clover (Lespedeza capitata) in fruit.

Crown vetch is an common and abundant roadside weed.